From. Public Domain Review

Deadly fogs, moralistic diatribes, debunked medical theory – Brett Beasley explores a piece of Victorian science fiction considered to be the first modern tale of urban apocalypse.

This is the way the world ends: not with a bang but a bronchial spasm. That is, at least, according to William Delisle Hay’s 1880 novellaThe Doom of the Great City. It imagines the entire population of London choked to death under a soot-filled fog. The story is told by the event’s lone survivor sixty years later as he recalls “the greatest calamity that perhaps this earth has ever witnessed” at what was, for Hay’s first readers, the distant future date of 1942.

The novella received only mild acclaim among its late Victorian readers, and today it is almost forgotten. But, surprisingly enough, it has become possible to read our social and environmental problems foretold in Hay’s strange little story. In our age of global warming, acid rain, and atmospheric pollution, we may become the first readers to take Hay seriously. When Hay imagines a city whose wealth and “false social system” lulls it into complacency, we can recognize ourselves in his words. And as for those air problems that loomed dangerously around them, Londoners “looked upon them in the light of a regular institution, not caring to investigate their cause with a view to some means of mitigating them”. At moments like these, we get the feeling that Hay’s obscure 135-year-old story is eerily prophetic.

But before we canonize Hay as an environmentalist and his story as An Inconvenient Truth in Victorian garb, we have to look at the story’s other features. Readers of The Doom of the Great City unfailingly notice that the story does not fit easily with other science fiction narratives, but seems to belong also to another class of tales, which Brian Stableford has called “ringing accounts of richly deserved punishment”. This is because Hay’s narrator seems to slide back and forth between material and moral explanations for pollution. While he talks of how “In those latter days there had been past years of terribly bad weather, destroying harvests”, he adds in the same paragraph, “prostitution flourished rampantly, while Chastity laid down her head and died! Evil! — one seemed to see it everywhere!”

In fact, the narrator goes so far as to cast himself as a prophet. Like a latterday Jeremiah he reviles London as “foul and rotten to the very core, and steeped in sin of every imaginable variety”. In a twenty-page diatribe he catalogues vices such as prodigality, corruption, avarice, and aestheticism — not to mention feminine vanity, for which he reserves special scorn. He denounces tradesmen, aristocrats, theater-goers, and the young as well as the old. For him, London is like Atlantis or Babylon standing blithely unaware of the divine wrath about to strike it.

All of this raises an important question: can pollution be material (i.e. made of soot, ashes, smoke, chemicals, etc.) and moral as well? The same question could also be stated as a problem of genre. What exactly are we reading when we read The Doom of the Great City? Is it a forward-looking sci-fi tale about a dystopian future that may yet arrive? Or is it a fantasy of divine retribution that belongs with the ancient past?

In order to answer that question, we need a working definition of science fiction. For that definition we could look to Rod Serling’s statement that science fiction is “the improbable made possible”. Hay certainly draws from available scientific ideas to make his improbable story into a reasonable possibility. Hay’s contemporary F. A. R. Russell consistently noted higher instances of death from asthma and respiratory complaints during intense fogs, and he published widely in an effort to raise public concern about them. But Hay’s literary precursors (like the public in general) tended to see the fog as a mere nuisance. They could even at times show some fanciful tenderness toward it as toward an ugly pet that won’t go away. For example, William Guppy in Dickens’ 1853 novel Bleak House describes the fog in familiar terms as “The London Particular”. But Hay makes that seemingly friendly pet bite — and, increasingly, the data was on his side.

In addition to the evidence of news and anecdotes, Hay needed a plausible cause of death, not just for the infirm, but for an entire metropolitan population. That is where the “bronchial spasm” comes in. Hay, a published scientist (specifically a mycologist) is scrupulous on this point. On the chance journey into the country that saves his life, Hay’s protagonist discusses the fog with a friend who also happens to be a leading medical authority, one Wilton Forrester. Forrester gives “the benefit of his scientific acquirements,” (emphasis mine) by laying out what he considers to be the only possible scenario in which a fog can prove fatal. He explains that in a case he previously observed

Hay goes so far as to include footnotes referencing actual medical authorities on this point. Rather than seeming far-fetched, Hay’s first readers could hardly have doubted that, past a certain threshold of pollution, a fog would certainly prove fatal to those who inhaled it.

Deadly fogs, moralistic diatribes, debunked medical theory – Brett Beasley explores a piece of Victorian science fiction considered to be the first modern tale of urban apocalypse.

|

| Coloured aquatint, ca. 1862, depicting a man covering his mouth with a handkerchief, walking through a smoggy London street – Source: Wellcome Library |

This is the way the world ends: not with a bang but a bronchial spasm. That is, at least, according to William Delisle Hay’s 1880 novellaThe Doom of the Great City. It imagines the entire population of London choked to death under a soot-filled fog. The story is told by the event’s lone survivor sixty years later as he recalls “the greatest calamity that perhaps this earth has ever witnessed” at what was, for Hay’s first readers, the distant future date of 1942.

The novella received only mild acclaim among its late Victorian readers, and today it is almost forgotten. But, surprisingly enough, it has become possible to read our social and environmental problems foretold in Hay’s strange little story. In our age of global warming, acid rain, and atmospheric pollution, we may become the first readers to take Hay seriously. When Hay imagines a city whose wealth and “false social system” lulls it into complacency, we can recognize ourselves in his words. And as for those air problems that loomed dangerously around them, Londoners “looked upon them in the light of a regular institution, not caring to investigate their cause with a view to some means of mitigating them”. At moments like these, we get the feeling that Hay’s obscure 135-year-old story is eerily prophetic.

But before we canonize Hay as an environmentalist and his story as An Inconvenient Truth in Victorian garb, we have to look at the story’s other features. Readers of The Doom of the Great City unfailingly notice that the story does not fit easily with other science fiction narratives, but seems to belong also to another class of tales, which Brian Stableford has called “ringing accounts of richly deserved punishment”. This is because Hay’s narrator seems to slide back and forth between material and moral explanations for pollution. While he talks of how “In those latter days there had been past years of terribly bad weather, destroying harvests”, he adds in the same paragraph, “prostitution flourished rampantly, while Chastity laid down her head and died! Evil! — one seemed to see it everywhere!”

|

| Front cover of Hay’s The Doom of the Great City – Source. |

In fact, the narrator goes so far as to cast himself as a prophet. Like a latterday Jeremiah he reviles London as “foul and rotten to the very core, and steeped in sin of every imaginable variety”. In a twenty-page diatribe he catalogues vices such as prodigality, corruption, avarice, and aestheticism — not to mention feminine vanity, for which he reserves special scorn. He denounces tradesmen, aristocrats, theater-goers, and the young as well as the old. For him, London is like Atlantis or Babylon standing blithely unaware of the divine wrath about to strike it.

All of this raises an important question: can pollution be material (i.e. made of soot, ashes, smoke, chemicals, etc.) and moral as well? The same question could also be stated as a problem of genre. What exactly are we reading when we read The Doom of the Great City? Is it a forward-looking sci-fi tale about a dystopian future that may yet arrive? Or is it a fantasy of divine retribution that belongs with the ancient past?

In order to answer that question, we need a working definition of science fiction. For that definition we could look to Rod Serling’s statement that science fiction is “the improbable made possible”. Hay certainly draws from available scientific ideas to make his improbable story into a reasonable possibility. Hay’s contemporary F. A. R. Russell consistently noted higher instances of death from asthma and respiratory complaints during intense fogs, and he published widely in an effort to raise public concern about them. But Hay’s literary precursors (like the public in general) tended to see the fog as a mere nuisance. They could even at times show some fanciful tenderness toward it as toward an ugly pet that won’t go away. For example, William Guppy in Dickens’ 1853 novel Bleak House describes the fog in familiar terms as “The London Particular”. But Hay makes that seemingly friendly pet bite — and, increasingly, the data was on his side.

|

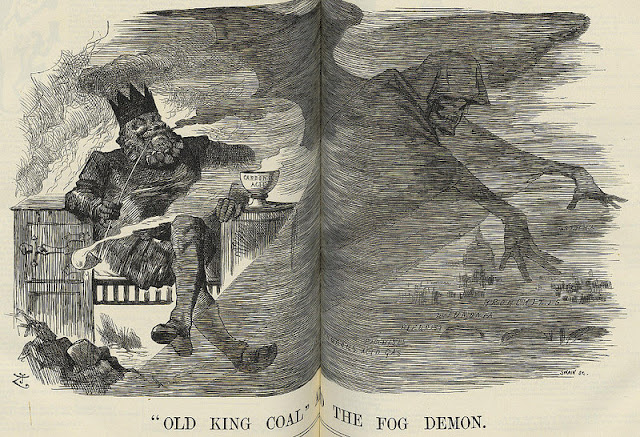

| ‘”Old king Coal” and the Fog Demon’, a cartoon featured in Punch, November 1880, the year in which Hay’s novella was published – Source: Universität Heidelberg. |

|

| Detail from the image above showing some of the fatal diseases London’s polluted fog could bring: pleurisy, pneumonia, bronchitis, and asmtha. |

The bronchi and tubes ramifying from them were clogged with black, grimy mucus, and death had evidently resulted from a sudden spasm, which would produce suffocation, as the lungs would not have the power in their clogged condition of making a sufficiently forcible expiatory effort to get rid of the accumulated filth that was the instrument of death.

Hay goes so far as to include footnotes referencing actual medical authorities on this point. Rather than seeming far-fetched, Hay’s first readers could hardly have doubted that, past a certain threshold of pollution, a fog would certainly prove fatal to those who inhaled it.

|

| Front cover for a 1913 booklet advertising Peps tablets for coughs and colds brought on by smog. A skull-faced Death appears in a swirling cloud of pollution over a city from which terrified inhabitants are fleeing – Source: Wellcome Library. |

Read the full article at : http://publicdomainreview.org/2015/09/30